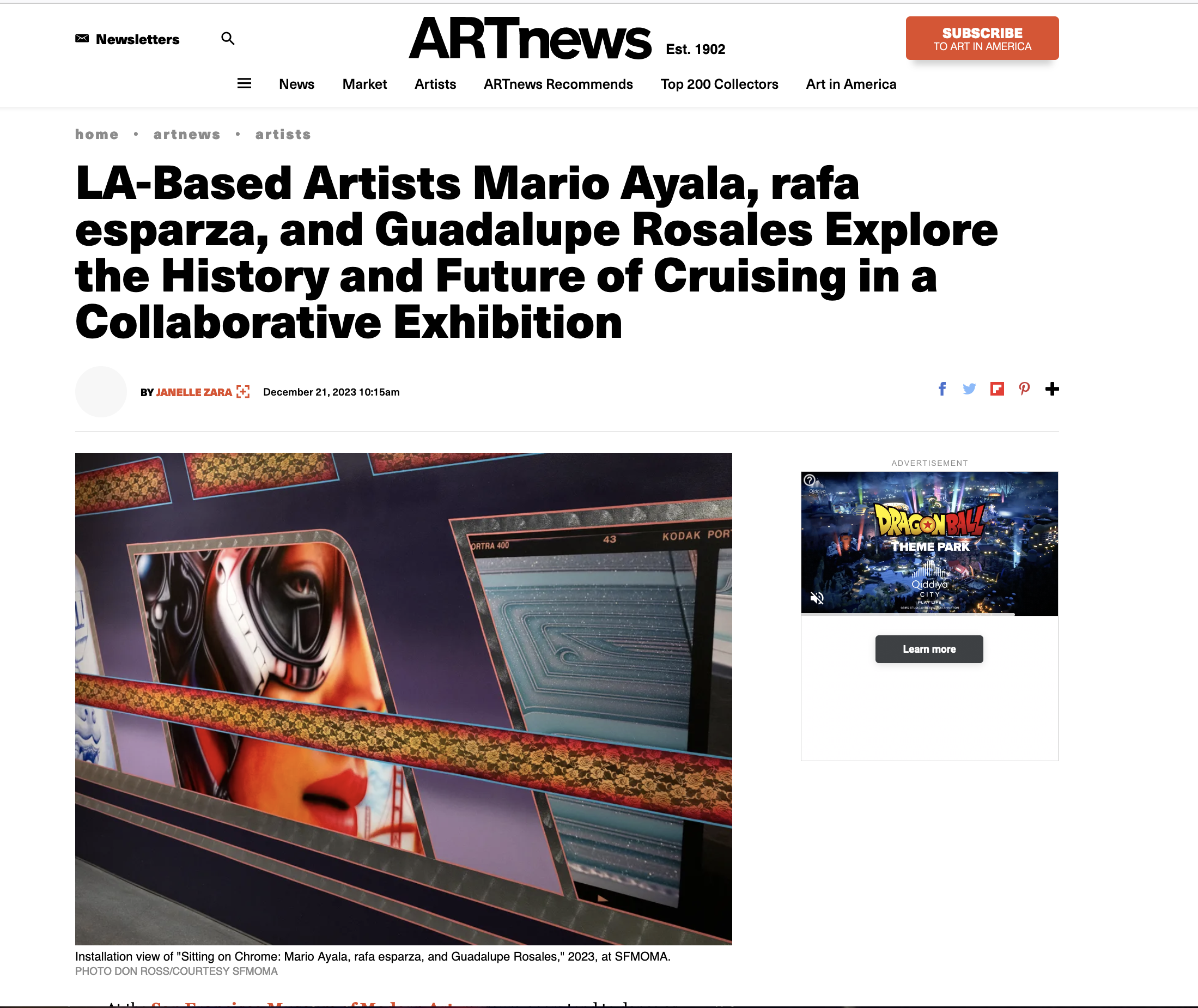

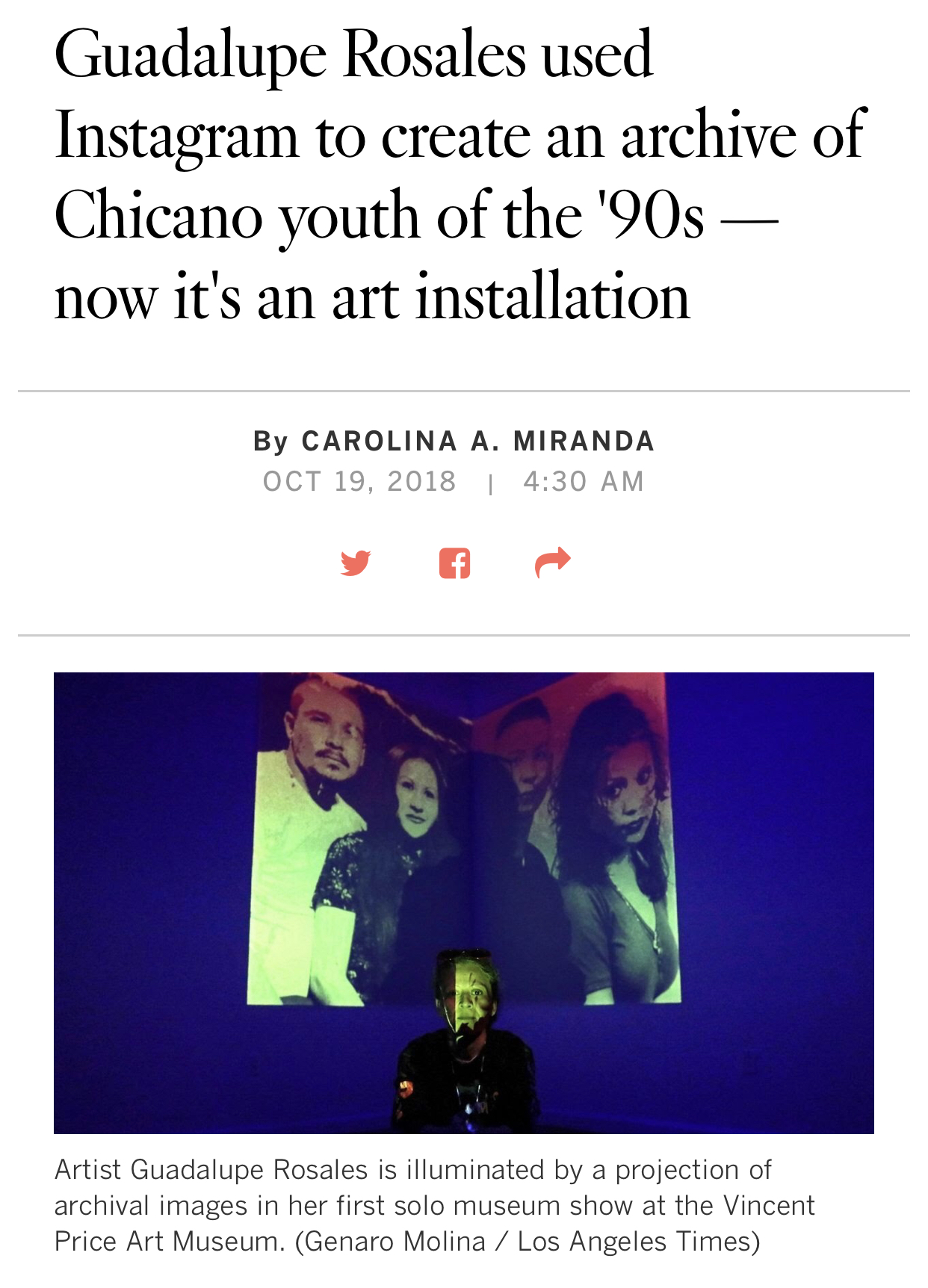

I was gonna make a room [that evokes my childhood bedroom]. But I wanted to be more porous and more part of the show, so instead of having a drywall room, I made it a skeleton, a steel frame. I want to invoke the absence of memory or absence of experience. My whole practice has been so much about the eerie, ghostly longing of these times, rather than being so formal and rigid. I’m also bringing in my portals that I’ve been making for quite some time now, but these are new. They are engraved polished aluminum and one of the portals says lyrics of a song — “I’ll smile for my friends and cry later.” And then inside the portals, I also have some archival material like newspaper articles from the L.A. Riots, a bandanna, things that are representative of my childhood. I wanted to make it a little bit more playful.

I think people tend to group us together because of who we are and what kind of art we make and where we’re from. And we’re all different. That’s the beautiful thing about the show — that everyone is bringing something different. But then we’re gonna have some connections. We’ll be able to see that in the show. I like to think of it as this constellation — where the ring gets bigger but you’re still connected somehow.

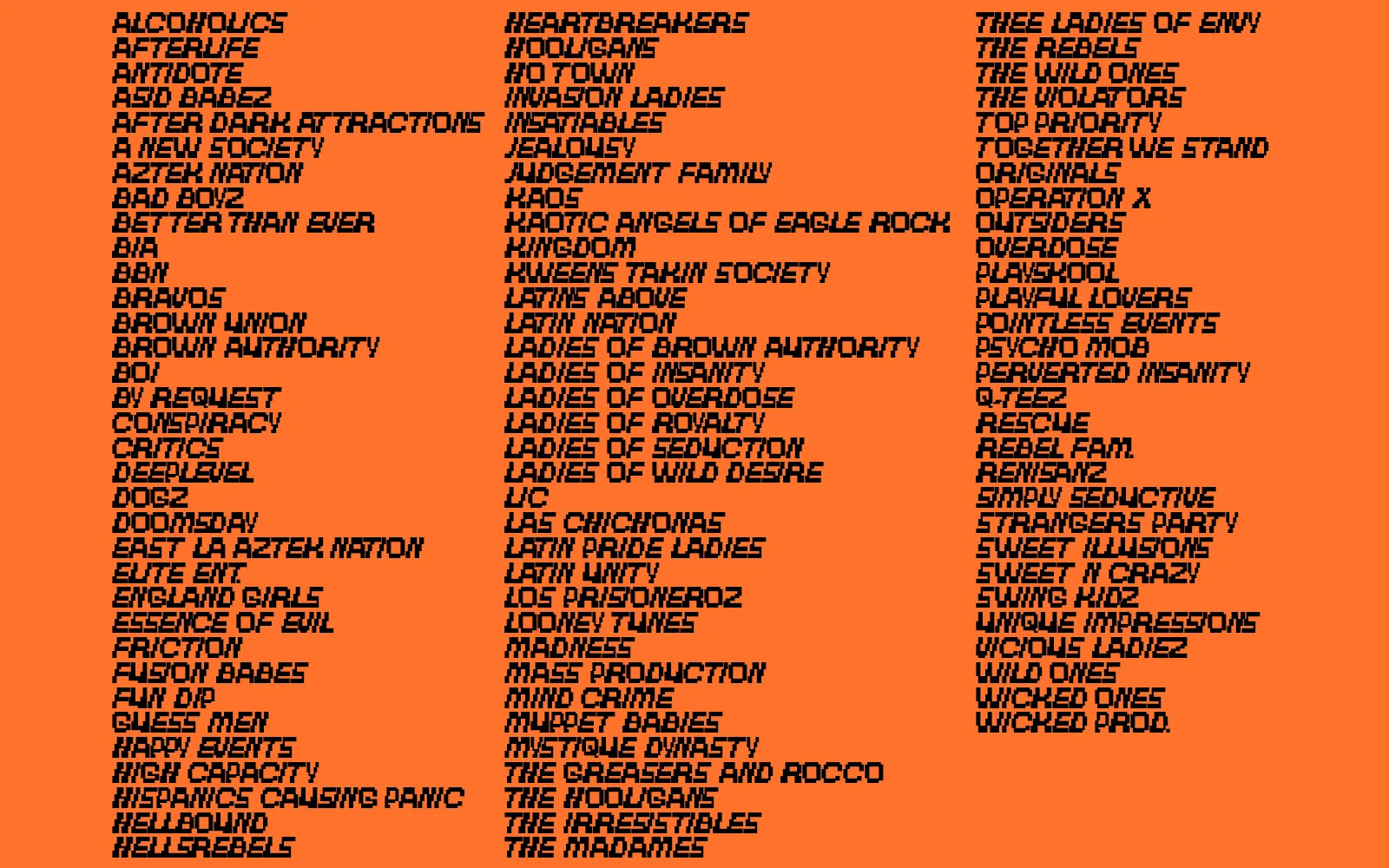

What makes up L.A.? For me, it’s alleyways, dark corners. It’s not just these landmarks of the bar or the club. It’s more about things that resonate. A lot of the people in the show can appreciate that — they know what I’m talking about, and vice versa. Painting these billboards, or being inspired by them — we recognize that as an L.A. moment. It’s almost these gestures or clues that we drop in our practices. I think it’s so special what’s happening now, because finally, we’re being recognized. Not just as artists, but as part of culture, American culture.